- Home

- Lloyd Alexander

The Book of Three Page 9

The Book of Three Read online

Page 9

Taran looked at the eager face of Gurgi. For the first time they smiled at one another.

“Your gift is generous,” Taran said softly, “but you travel as one of us and you will need all your strength. Keep your share; it is yours by right; and you have more than earned it.”

He put his hand gently on Gurgi’s shoulder. The wet wolfhound odor did not seem as objectionable as before.

CHAPTER TWELVE

The Wolves

For a time, during the day, Taran believed they had at last outdistanced the Cauldron-Born. But, late that afternoon, the warriors reappeared from behind a distant fringe of trees. Against the westering sun, the long shadows of the horsemen reached across the hill slope toward the flatlands where the small troop struggled onward.

“We must stand against them sooner or later,” Taran said, wiping his forehead. “Let it be now. There can be no victory over the Cauldron-Born, but with luck, we can hold them off a little while. If Eilonwy and Gurgi can escape, there is still a chance.”

Gurgi, draped over Melyngar’s saddle, immediately set up a great outcry. “No, no! Faithful Gurgi stays with mighty lord who spared his poor tender head! Happy, grateful Gurgi will fight, too, with slashings and gashings …”

“We appreciate your sentiments,” said Fflewddur, “but with that leg of yours, you’re hardly up to slashing or gashing or anything at all.”

“I’m not going to run, either,” Eilonwy put in. “I’m tired of running and having my face scratched and my robe torn, all on account of those stupid warriors.” She jumped lightly from the saddle and snatched a bow and a handful of arrows from Taran’s pack.

“Eilonwy! Stop!” Taran cried. “These are deathless men! They cannot be killed!”

Although encumbered by the long sword hanging from her shoulder, Eilonwy ran faster than Taran. By the time he caught up with her, she had climbed a hillock and was stringing the bow. The Cauldron-Born galloped across the plain. The sun glinted on their drawn swords.

Taran seized the girl by the waist and tried to pull her away. He received a sharp kick in the shins.

“Must you always interfere with everything?” Eilonwy asked indignantly.

Before Taran could reach for her again, she held an arrow toward the sun and murmured a strange phrase. She nocked the arrow and loosed it in the direction of the Cauldron-Born. The shaft arched upward and almost disappeared against the bright rays.

Open-mouthed, Taran watched while the shaft began its descent: as the arrow plummeted to earth, long, silvery streamers sprang from its feathers. In an instant, a huge spiderweb glittered in the air and drifted slowly toward the horsemen.

Fflewddur, who had run up just then, stopped in amazement. “Great Belin!” he exclaimed. “What’s that? It looks like decorations for a feast!”

The web slowly settled over the Cauldron-Born, but the pallid warriors paid it no heed. They spurred their mounts onward; the strands of the web broke and melted away.

Eilonwy clapped a hand to her mouth. “It didn’t work!” she cried, almost in tears. “The way Achren does it, she makes it into a big sticky rope. Oh, it’s all gone wrong. I tried to listen behind the door when she was practicing, but I’ve missed something important.” She stamped her foot and turned away.

“Take her from here!” Taran called to the bard. He unsheathed his sword and faced the Cauldron-Born. Within moments they would be upon him. But, even as he braced for their onslaught, he saw the horsemen falter. The Cauldron-Born reined up suddenly; then, without a gesture, turned their horses and rode silently back toward the hills.

“It worked! It worked after all!” cried the astonished Fflewddur.

Eilonwy shook her head. “No,” she said with discouragement, “something turned them away, but I’m afraid it wasn’t my spell.” She unstrung the bow and picked up the arrows she had dropped.

“I think I know what it was,” Taran said. “They are returning to Arawn. Gwydion told me they could not stay long from Annuvin. Their power must have been waning ever since we left Spiral Castle, and they reached the limit of their strength right here.”

“I hope they don’t have enough to get back to Annuvin,” Eilonwy said. “I hope they fall into pieces or shrivel up like bats.”

“I doubt that they will,” Taran said, watching the horsemen slowly disappear over the ridge. “They must know how long they can stay and how far they can go, and still return to their master.” He gave Eilonwy an admiring glance. “It doesn’t matter. They’re gone. And that was one of the most amazing things I’ve ever seen. Gwydion had a mesh of grass that burst into flame; but I’ve never met anyone else who could make a web like that.”

Eilonwy looked at him in surprise. Her cheeks blushed brighter than the sunset. “Why, Taran of Caer Dallben,” she said, “I think that’s the first polite thing you’ve said to me.” Then, suddenly, Eilonwy tossed her head and sniffed. “Of course, I should have known; it was the spiderweb. You were more interested in that; you didn’t care whether I was in danger.” She strode haughtily back to Gurgi and Melyngar.

“But that’s not true,” Taran called. “I—I was …” By then, Eilonwy was out of earshot. Crestfallen, Taran followed her. “I can’t make sense out of that girl,” he said to the bard. “Can you?”

“Never mind,” Fflewddur said. “We aren’t really expected to.”

That night, they continued to take turns at standing guard, though much of their fear had lifted since the Cauldron-Born had vanished. Taran’s was the last watch before dawn, and he was awake well before Eilonwy’s had ended.

“You had better sleep,” Taran told her. “I’ll finish the watch for you.”

“I’m perfectly able to do my share,” said Eilonwy, who had not stopped being irritated at him since the afternoon.

Taran knew better than to insist. He picked up his bow and quiver arrows, stood near the dark trunk of an oak, and looked out across the moon-silvered meadow. Nearby, Fflewddur snored heartily. Gurgi, whose leg had shown no improvement, stirred restlessly and whimpered in his sleep.

“You know,” Taran began, with embarrassed hesitation, “that spiderweb …”

“I don’t want to hear any more about it,” retorted Eilonwy.

“No—what I meant was: I really was worried about you. But the web surprised me so much I forgot to mention it. It was courageous of you to stand up against the Cauldron warriors. I just wanted to tell you that.”

“You took long enough getting around to it,” said Eilonwy, a tone of satisfaction in her voice. “But I imagine Assistant Pig-Keepers tend to be slower than what you might expect. It probably comes from the kind of work they do. Don’t misunderstand, I think it’s awfully important. Only it’s the sort of thing you don’t often need to be quick about.”

“At first,” Taran went on, “I thought I would be able to reach Caer Dathyl by myself. I see now that I wouldn’t have got even this far without help. It is a good destiny that brings me such brave companions.”

“There, you’ve done it again,” Eilonwy cried, so heatedly that Fflewddur choked on one of his snores. “That’s all you care about! Someone to help you carry spears and swords and what-all. It could be anybody and you’d be just as pleased. Taran of Caer Dallben, I’m not speaking to you any more.”

“At home,” Taran said—to himself, Eilonwy had already pulled a cloak over her head and was feigning sleep—“nothing ever happened. Now, everything happens. But somehow I can never seem to make it come out right.” With a sigh, he held his bow ready and began his turn at guard. Daylight was long in coming.

In the morning, Taran saw Gurgi’s leg was much worse, and he left the campsite to search the woods for healing plants, glad that Coll had taught him the properties of herbs. He made a poultice and set it on Gurgi’s wound.

Fflewddur, meanwhile, had begun drawing new maps with his dagger. The Cauldron warriors, explained the bard, had forced the companions too deeply into the Ystrad valley. Returning to their origi

nal path would cost them at least two days of hard travel. “Since we’re this far,” Fflewddur went on, “we might just as well cross Ystrad and follow along the hills, staying out of sight of the Horned King. We’ll be only a few days from Caer Dathyl, and if we keep a good pace, we should reach it just in time.”

Taran agreed to the new plan. It would, he realized, be more difficult; but he judged Melyngar could still carry the unfortunate Gurgi, as long as the companions shared the burden of the weapons. Eilonwy, having forgotten she was not speaking to Taran, again insisted on walking.

A day’s march brought them to the banks of the Ystrad.

Taran stole cautiously ahead. Looking down the broad valley, he saw a moving dust cloud. When he hurried back and reported this to Fflewddur, the bard clapped him on the shoulder.

“We’re ahead of them,” he said. “That is excellent news. I was afraid they’d be much closer to us and we’d have to wait for nightfall to cross Ystrad. We’ve saved half a day! Hurry now and we’ll be into the foothills of Eagle Mountains before sundown!”

With his precious harp held above his head, Fflewddur plunged into the river, and the others followed. Here, the Ystrad ran shallow, scarcely above Eilonwy’s waist, and the companions forded it with little difficulty. Nevertheless, they emerged cold and dripping, and the setting sun neither dried nor warmed them.

Leaving the Ystrad behind, the companions climbed slopes steeper and rockier than any they had traveled before. Perhaps it was only his imagination, but the air of the land around Spiral Castle had seemed, to Taran, heavy and oppressive. Approaching the Eagle Mountains, Taran felt his burden lighten, as he inhaled the dry, spicy scent of pine.

He had planned to continue the march throughout most of the night; but Gurgi’s condition had worsened, obliging Taran to call a halt. Despite the herbs, Gurgi’s leg was badly inflamed, and he shivered with fever. He looked thin and sad; the suggestion of crunchings and munchings could not rouse him. Even Melyngar showed concern. As Gurgi lay with his eyes half-closed, his parched lips tight against his teeth, the white mare nuzzled him delicately, whinnying and blowing out her breath anxiously, as if attempting to comfort him as best she could.

Taran risked lighting a small fire. He and Fflewddur stretched Gurgi out beside it. While Eilonwy held up the suffering creature’s head and gave him a drink from the leather flask, Taran and the bard moved a little away and spoke quietly between themselves.

“I have done all I know,” Taran said. “If there is anything else, it lies beyond my skill.” He shook his head sorrowfully. “He has failed badly today, and there is so little of him left I believe I could pick him up with one hand.”

“Caer Dathyl is not far away,” said Fflewddur, “but our friend, I fear, may not live to see it.”

That night, wolves howled in the darkness beyond the fire.

All next day, the wolves followed them; sometimes silently, sometimes barking as if in signal to one another. They remained always out of bow shot, but Taran caught sight of the lean, gray shapes flickering in and out of the scrubby trees.

“As long as they don’t come any closer,” he said to the bard, “we needn’t worry about them.”

“Oh, they won’t attack us,” Fflewddur answered. “Not now, at any rate. They can be infuriatingly patient if they know someone’s wounded.” He turned an anxious glance toward Gurgi. “For them, it’s just a matter of waiting.”

“Well, I must say you’re a cheerful one,” remarked Eilonwy. “You sound as if all we had to look forward to was being gobbled up.”

“If they attack, we shall stand them off,” Taran said quietly. “Gurgi was willing to give up his life for us; I can do no less for him. Above all, we must not lose heart so close to the end of our journey.”

“A Fflam never loses heart!” cried the bard. “Come wolves or what have you!”

Nevertheless, uneasiness settled over the companions as the gray shapes continued trailing them; and Melyngar, docile and obedient until now, turned skittish. The golden-maned horse tossed her head and rolled her eyes at every attempt to lead her.

To make matters worse, Fflewddur declared their progress through the hills was too slow.

“If we go any farther east,” said the bard, “we’ll run into some really high mountains. The condition we’re in, we couldn’t possibly climb them. But here, we’re practically walled in. Every path has led us roundabout. The cliffs there,” he went on, pointing toward the towering mass of rock to his left, “are too rugged to get over. I had thought we’d find a pass before now. Well, that’s the way of it. We can only keep on bearing north as much as possible.”

“The wolves didn’t seem to have any trouble finding their way,” said Eilonwy.

“My dear girl,” answered the bard, with some indignation, “if I were able to run on four legs and sniff my dinner a mile away, I doubt I’d have any difficulties either.”

Eilonwy giggled. “I’d love to see you try,” she said.

“We do have someone who can run on four legs,” Taran said suddenly. “Melyngar! If anyone can find their way to Caer Dathyl, she can.”

The bard snapped his fingers. “That’s it!” he cried. “Every horse knows its way home! It’s worth trying—and we can’t be worse off than we are now.”

“For an Assistant Pig-Keeper,” said Eilonwy to Taran, “you do come up with some interesting ideas now and then.”

When the companions started off again, Taran dropped the bridle and gave Melyngar her head. With the half-conscious Gurgi bound to her saddle, the white horse trotted swiftly ahead at a determined gait.

By mid-afternoon, Melyngar discovered one pass which, Fflewddur admitted, he himself would have overlooked. As the day wore on, Melyngar led them swiftly through rocky defiles to high ridges. It was all the companions could do to keep up with her. When she cantered into a long ravine, Taran lost sight of her for a moment and hurried forward in time to glimpse the mare as she turned sharply around an outcropping of white stone.

Calling the bard and Eilonwy to follow quickly, Taran ran ahead. He stopped suddenly. To his left, on a high shelf of rock, crouched an enormous wolf with golden eyes and lolling red tongue. Before Taran could draw his sword, the lean animal sprang.

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

The Hidden Valley

The impact of the heavy, furry body caught Taran full in the chest, and sent him tumbling. As he fell, he caught a glimpse of Fflewddur. The bard, too, had been borne to earth under the paws of another wolf. Eilonwy still stood, though a third animal crouched in front of her.

Taran’s hand flew to his sword. The gray wolf seized his arm. The animal’s teeth, however, did not sink into his flesh, but held him in an unshakable grip.

At the end of the ravine a huge, robed figure suddenly appeared. Melyngar stood behind him. The man raised his arm and spoke a command. Immediately, the wolf holding Taran relaxed his jaws and drew away, as obediently as a dog. The man strode toward Taran, who scrambled to his feet.

“You saved our lives,” Taran began. “We are grateful.”

The man spoke again to the wolves and the animals crowded around him, whining and wagging their tails. He was a strange-looking figure, broad and muscular, with the vigor of an ancient but sturdy tree. His white hair reached below his shoulders and his beard hung to his waist. Around his forehead he wore a narrow band of gold, set with a single blue jewel.

“From these creatures,” he said, in a deep voice that was stern but not unkind, “your lives were never in danger. But you must leave this place. It is not an abode for the race of men.”

“We were lost,” Taran said. “We had been following our horse …”

“Melyngar?” The man turned a pair of keen gray eyes on Taran. Under his deep brow they sparkled like frost in a valley. “Melyngar brought me four of you? I understood young Gurgi was alone. By all means, then, if you are friends of Melyngar. It is Melyngar, isn’t it? She looks so much like her mother; and there are so many

I cannot always keep track of the names.”

“I know who you are,” cried Taran. “You are Medwyn!”

“Am I now?” the man answered with a smile that furrowed his face. “Yes, I have been called Medwyn. But how should you know that?”

“I am Taran of Caer Dallben. Gwydion, Prince of Don, was my companion, and he spoke of you before—before his death. He was journeying to Caer Dathyl, as we are now. I never hoped to find you.”

“You were quite right,” Medwyn answered. “You could not have found me. Only the animals know my valley. Melyngar led you here. Taran, you say? Of Caer Dallben?” He put an enormous hand to his forehead. “Let me see. Yes, there are visitors from Caer Dallben, I am sure.”

Taran’s heart leaped. “Hen Wen!” he cried.

Medwyn gave him a puzzled glance. “Were you seeking her? Now, that is curious. No, she is not here.”

“But I had thought …”

“We will speak of Hen Wen later,” said Medwyn. “Your friend is badly injured, you know. Come, I shall do what I can for him.” He motioned for them to follow.

The wolves padded silently behind Taran, Eilonwy, and the bard. Where Melyngar waited at the end of the ravine, Medwyn lifted Gurgi from the saddle, as if the creature weighed no more than a squirrel. Gurgi lay quietly in Medwyn’s arms.

The group descended a narrow footpath. Medwyn strode ahead, as slowly and powerfully as if a tree were walking. The old man’s feet were bare, but the sharp stones and pebbles did not trouble him. The path turned abruptly, then turned again. Medwyn passed through a cut in a bare shoulder of the cliff, and the next thing Taran knew, they suddenly emerged into a green, sunlit valley. Mountains, seemingly impassable, rose on all sides. Here the air was gentler, without the tooth of the wind; the grass spread rich and tender before him. Set among tall hemlocks were low, white cottages, not unlike those of Caer Dallben. At the sight of them, Taran felt a pang of homesickness. Against the face of the slope behind the cottages, he saw what appeared at first to be rows of moss-covered tree trunks; as he looked, to his surprise, they seemed more like the weather-worn ribs and timbers of a long ship. The earth covered them almost entirely; grass and meadow flowers had sprung up to obliterate them further and make them part of the mountain itself.

The Foundling and Other Tales of Prydain

The Foundling and Other Tales of Prydain The Castle of Llyr

The Castle of Llyr Taran Wanderer (The Chronicles of Prydain)

Taran Wanderer (The Chronicles of Prydain) Taran Wanderer

Taran Wanderer The Iron Ring

The Iron Ring The Arkadians

The Arkadians Fifty Years in the Doghouse

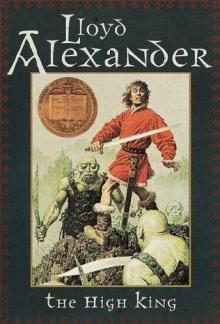

Fifty Years in the Doghouse The High King

The High King The Remarkable Journey of Prince Jen

The Remarkable Journey of Prince Jen The Book of Three

The Book of Three The Gawgon and the Boy

The Gawgon and the Boy The Illyrian Adventure

The Illyrian Adventure Westmark

Westmark The Black Cauldron

The Black Cauldron The Book of Three cop-1

The Book of Three cop-1 Taran Wanderer cop-4

Taran Wanderer cop-4 The Castle of Llyr cop-3

The Castle of Llyr cop-3 The High King (Chronicles of Prydain (Henry Holt and Company))

The High King (Chronicles of Prydain (Henry Holt and Company)) The High King cop-5

The High King cop-5 The Foundling

The Foundling The Castle of Llyr (The Chronicles of Prydain)

The Castle of Llyr (The Chronicles of Prydain)