- Home

- Lloyd Alexander

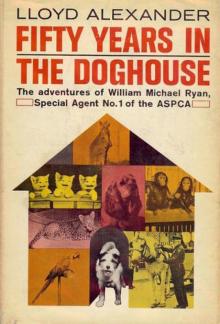

Fifty Years in the Doghouse

Fifty Years in the Doghouse Read online

EDITOR / CONVERTER NOTES

Thanks to whoever post the high quality PDF Scans of the original book. I converted it using Adobe Acrobat DC Pro to plain text file and edited it using Gutcheck and Notepad++ to remove most errors from the file then created the ePUB using Sigil. As all ways this is not 100% perfect without a proper proof read so there will be the odd mistake. Enjoy the book and remember support the author if you like it.

- EyesOnly

Fifty Years in the Doghouse

by Lloyd Alexander

Author's Note

THE American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals has another branch of operations: Kindness to Authors, which provides everything an author could want in the way of cooperation and encouragement. Bill Ryan is a man not only of infinite resource but also of patience. From his own literary experience, the Society's Administrative Vice-President, William Mapel, has developed a special intuition about another author's needs. My thanks, also, must go to William Rockefeller, the Society's President, and to the divisional directors: Arthur L. Amundsen, ASPCA Operations; Colonel Edmond M. Rowan, Humane Work; Mrs. George Fielding Eliot, Publications and Programs; Dr. John E. Whitehead, Hospital and Clinic; Thomas A. Fegan, Comptroller; and a particular note of gratitude to Jay Beyersdorf and Janice Paprin. For them, nothing has been too much trouble, nothing has demanded too much time. To them, and to all the Society staff, active and retired, who willingly shared their knowledge and experience with me, I should like to express my sincerest appreciation.

L.A.

1 - Is There a Toad in Your Cornerstone?

If an elephant ever decided to reveal the whereabouts of the Elephants' Graveyard, he would tell his secret to a man named William Michael Ryan, of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Big, blue-eyed, white-haired, with a deft pair of hands and a smile that looks three feet wide, Ryan knows pretty much all there is to know about making friends with animals. Perhaps this is a special blessing of the Irish. Whatever the gift, Ryan has been an ASPCA special agent for fifty years-the longest anyone has served continuously with the Society since its founding in 1866. From ASPCA headquarters in New York City, as one of the organization's seventeen uniformed agents, Ryan has coped with something like half a million beasts, birds and reptiles. Most of them were in trouble. Getting them out has been a matter of life or death: the animals'-and sometimes Ryan's. From what Ryan has seen, the animals are still trying to figure us out. Although the animals generally like us personally, they haven't entirely come to terms with our gadgets, architecture and other handiwork. A cat sometimes mistakes a chimney for a brick-lined mouse hole and gets trapped in it. Rush-hour traffic can drive a dog to despair.

A horse finds himself unintentionally in somebody's living room. Chimpanzees wake up in boardinghouse beds. A bull suddenly materializes in a powder room. Lions with no pressing engagements may stroll through Manhattan. The situations are not always that grave. In some cases, a human, not an animal, presents the larger problem. One busy afternoon, a carpenter working on a new building in the East Fifties phoned Ryan to advise about a cornerstone laying ceremony. "Listen," the carpenter said, "these people are plastering up a toad in that cornerstone. I know it's only a toad and all that. But I mean, what the hell-it doesn't seem right. And the toad sure doesn't like it!" This was Ryan's first call involving a toad. Nevertheless, a toad, as far as Ryan and the ASPCA were concerned, rated as much consideration as any other creature. "Stay there," Ryan told the carpenter. "I'm on my way." Ryan drove through traffic with a dispatch a cabbie would have envied. He found the carpenter waiting at the corner. The new building, the carpenter explained, belonged to Madame Charmaine, a famous Parisian fashion designer. As the carpenter had heard, Madame Charmaine believed the superstition that a toad in a cornerstone brings good luck. She now intended putting it to the test. Ryan headed for the front of the building and made his way through the crowd of well-wishers. The guests of honor, Ryan discovered later, included the French Consul General and several other dignitaries. Madame Charmaine, in one of her newest creations, waved a silver trowel. Ryan stands a little under six feet, but when an animal is in any kind of danger he seems about eight feet four. The policeman-style cap, dark uniform and pistol on his hip may account for some of this impressiveness, although Ryan would look impressive walking around wearing a barrel. He stopped before Madame Charmaine and, in a calm, patient voice, as if he had asked the same question a thousand times before, he said, "Madam, is there a toad in your cornerstone?" Madame Charmaine was as noted for her Gallic temperament as for her fashions.

When she finally calmed down enough to speak English, she demanded to know whose affair it was, this toad! What Madame Charmaine chose to put in her cornerstone concerned no one but Madame Charmaine herself. Ryan admitted this was generally true. In the pure accent of New York, he tried to convey to the excited Frenchwoman that walling up a live toad could be reasonably construed as cruelty. Under New York State law, Ryan is empowered to act in such cases. Ryan has his own Irish temper and vocabulary which he uses when he has to; much of the time, he relies on a touch of blarney. It usually works as well on humans as it does on animals. It did not work with Madame Charmaine. "You will do me the favor to get out," she cried. "Leave! intermediate!" Unruffled, Ryan tipped his cap politely. "See you in court," he said. By this time a dark-suited, gray-haired man had come up beside Madame Charmaine. He was, it turned out, one of her lawyers. He called Ryan back: "Listen, officer, this is a joke, isn't it?" Ryan assured him he was quite serious. He also pointed out that if Madame Charmaine went ahead with her cornerstone and the builders went ahead with their building, the fashion designer might find herself obliged to tear down several walls. It would be easier to remove the toad now while the removing was good. The lawyer whispered hurriedly in Madame Charmaine's ear. With a furious glance at Ryan, the fashion designer uncapped the cornerstone and brought out the prisoner.

Ryan had been expecting a garden toad. What emerged was the biggest Texas horned toad he had ever seen. "All right," said the lawyer, "he's out. Now what do you want?" Ryan offered to take the former captive back to one of the ASPCA shelters. The six in New York City have housed everything from three-day-old kittens to full-grown lions, and a horned toad, even a Texas one, would hardly have caused a stir. Wild animals usually get returned to their natural environments; but others are available for adoption and Ryan felt sure someone in Manhattan would be looking for a horned toad. This seemed plausible to the lawyer. Madame Charmaine took a different view. "Eh bien, that toad still belongs to me," she said angrily. "He is my property. I do not have to give him to anybody." Ryan agreed. Madame Charmaine had every right to keep the toad-as long as she looked after it properly. The only question was: did Madame Charmaine have the kind of facilities a toad would enjoy? If not, she might still be charged with cruelty. "Go away!" Madame Charmaine shouted. "I do what I want with my toad! C'est ridicule!"

"I think," said the lawyer, "we'd better talk this over." Still fuming, Madame Charmaine led the lawyer and Ryan to her original building a few doors down the street and ushered them into her office. Hardly in a frame of mind to play the gracious hostess, Madame Charmaine put the toad on her desk. A horned toad looks like one of Nature's practical jokes. It has the color of sand and rock; its edges are fringed, as if a dressmaker had trimmed it out with pinking shears. Spiky scales run down its back, and horns jut from its head. But none of this exists for amusement. The horns discourage snakes from swallowing the toad and are thus an important accessory as far as the toad is concerned. With its fringed edges, the toad can dig itself quickly into the sand, using a kind of back-beat double-shuffle not unlike certain modern dances. T

he color is excellent camouflage. The toad was considerably more functional than most of Madame Charmaine's fabrications-and Madame Charmaine recognized good design when she saw it. "You know," Madame Charmaine said, "he is very interesting, this toad. He is very well arranged."

"Wouldn't you say he deserved a better break than being suffocated in your cornerstone?" Ryan asked. When frightened, horned toads play dead. This one had been doing so ever since Madame Charmaine had released him. Now he ventured to open an eye and glance wearily about him. "Tiens, he winked at me!" said Madame Charmaine delightedly. "He is an agreeable one." She looked at the toad again. "Non," she added, "it would not be just to lock him in the cornerstone. He is mine and he will stay with me." That was all very well, Ryan said. But a toad wasn't a mechanical toy. It had to have a place to live and it had to eat. Madame Charmaine raised an eyebrow. The toad's menu had never occurred to her. "What does he eat?" she asked Ryan. "Oh, grubs and things, meal worms probably," Ryan said. Madame Charmaine's expression changed and she gave a shudder. "Worms?"

"What do you expect him to eat?" Ryan asked. "Crepes Suzette?"

"Do you wish to say then," Madame Charmaine cried, "that I must search New York for worms?"

"You might get by on hamburger," Ryan said. "Toads!" Madame Charmaine said in despair. "Why must they be so complicated?"

"He was doing fine in Texas," Ryan said.

Madame Charmaine thought for a while. "Eh bien," she said, "if he must have the worms, he will have them." The lawyer looked much relieved. Everyone shook hands all around. "Tell me, just between us," the lawyer said to Ryan. "Madame Charmaine's going to keep this toad and she's going to look after it. I don't know why, but she's taken a liking to it. So everything's all right, as far as that goes. But what I want to know is this: if she hadn't gone along with you-just suppose she'd plastered up that cornerstone would you really have made her take the building apart?" The ASPCA agent grinned at him. Ryan, when he wants to convey important or confidential information, has a way of tilting his head to one side and lowering his voice. He drew a little closer to the lawyer. "Damned right I would have," he said. As Ryan was about to leave the office, Madame Charmaine stopped him. "Monsieur," she said, "you are a most unusual man. In all this affair about a toad, I look at him and I see him for the first time. I see he is a gorgeous toad, more clever than anything even I could do. And I think, yes, this man is right. So, if this little animal is important to him, it must be important to me, too." The last Ryan heard was that Madame Charmaine had installed the toad in her penthouse, in a sunny, pebbled garden. It was a more exotic atmosphere than Texas, but the toad seemed to be enjoying it; which, as far as Ryan was concerned, was all that counted. Another of Ryan's cases brought him even closer to taking a building apart. It concerned a horse, not a toad. The horse was not in a cornerstone but in a situation no less complicated: under a flight of steps. A few years ago, when horse-drawn vehicles were more common in Manhattan than they are now, a deliveryman's horse bolted. No one knew exactly what had frightened the animal in the first place. Whatever it was, the horse must have felt he would be better off under cover.

After galloping down the street, kicking the wagon to pieces as if it had been a matchbox and breaking loose from his harness, the horse found sanctuary under the stairwell of one of the old brownstone houses. Police called Ryan to the scene because more ingenuity was involved than simply leading the horse out again. The landlady, who lived in a basement apartment, stored empty rubbish cans under the stairwell. When Ryan arrived he saw that the horse had managed to get his hind legs stuck in two of the cans. The horse whinnied and rolled his eyes frantically. At first, Ryan imagined the animal only to be frightened. But even after the horse had calmed down, Ryan realized it was impossible to make him move. For all the weight they carry, a horse's legs are delicate. Perhaps horses realize this themselves for they are terrified of anything that may harm their legs or throw them off balance. A pair of attached rubbish cans seemed ample reason for the horse to stay right where he was. Crouched headfirst under the stairwell, as if playing some equine game of hide-and-seek, the horse turned and peered woefully at Ryan. Ryan peered back just as woefully. As far as the police officers could see at the moment, the only way to extricate the horse was to tear down the stairs. Meantime, the landlady kept waving her arms and complaining that New York was no place for law-abiding people. One of the policemen pushed his cap to the back of his head and put his hands on his hips. "Well," he said, "we'd better get some workmen out here with sledgehammers." He glanced at the stone steps. "It shouldn't take much to knock 'em down." This did not quiet the landlady in the slightest. "Knock down the steps, is it?" she cried.

"That's all right for the horse-he doesn't have to live here!"

"Wait a minute," Ryan said. He had been studying the horse's position carefully. "You might not have to touch those steps after all." Ryan had decided there was no way in the world to persuade the horse to back out of the stairwell. But he felt pretty sure he could make the horse go forward. However, the only place for the animal to go forward was into the living room. "You go inside," he told the landlady, "and open your door. I'll lead the horse in-"

"Oh no you won't!" the landlady exploded. "Take a horse into my living room? If you think you're going to." Ryan tried to explain that she had only two choices a horse temporarily in her living room or her steps permanently damaged. In any case, she could not leave the horse under the stairs. What, Ryan asked, would the tenants say? The idea of the tenants seemed to have a profound effect on the landlady. "Well." She hesitated. "All right, you can bring him in. But I warn you track dirt in my parlor and I'll have the law after you. I don't even let my husband in the living room with his shoes on!"

"Lady," said Ryan, "I promise you. You'll never see a speck of dust." Leaving the horse under the steps, quite sure the animal wouldn't move until he returned, Ryan went off in search of a ragman. ASPCA calls have taken Ryan into every neighborhood from Park Avenue to Hell's Kitchen; he has learned every nook and cranny, every shop and business. Finding a rag picker took him no time at all. When he did, Ryan asked for the loan of about fifty burlap bags. "Buddy," said the ragman, "I collect junk, I collect old clothes and bottles and scrap iron. I buy them, I sell them-but I don't lend them!"

"It's for a horse," Ryan said. "I'll bring them right back."

"Oh, for a horse. Sure," said the rag picker. "That explains everything. You want to make a nice suit for the horse. Look, mister, why don't you go find a custom tailor?" The rag picker softened a little after Ryan described the horse's plight. "Okay, okay," the man said. "I got a horse myself. Maybe you help him out someday." Loaded with burlap bags, Ryan raced back to the house. He spread the bags over the landlady's carpet. With a length of rope, he tied back the chandelier so it wouldn't knock against the horse's head. All Ryan needed was to have the animal bolt through the apartment. Afraid to look, the landlady opened the door. Very gently, Ryan led the horse, cans and all, into the living room. Inside, the horse appeared gigantic. The neighbors had gathered to watch the procedure. Unlike their mother, the landlady's children danced with glee. "Keep it quiet there," Ryan ordered. "The poor fellow's scared enough." He steadied the horse, lifted one of its hind legs out of the can. He removed the other can just as easily, turned the horse around, led the animal up the steps and into the street. The whole de-canning operation had taken about three minutes. Ryan untied the chandelier and rolled up the burlap bags. As he had promised, not a speck of dirt had soiled the landlady's rug. The owner, who eventually recovered his horse, was delighted. The landlady was delighted at getting the animal out of her living room, the policemen were delighted because the business was handled without a riot. The neighbors were gratified, and everyone, in fact, was pleased. Except the landlady's little boy. For a moment, he had believed his parents had finally decided to get him a pony.

2 - The Berghs-man

Ryan today is a muscular, jovial wall of a man and he gives the

feeling that whatever may be wrong is now going to be all right. Nothing rattles him and probably nothing ever did. At fourteen, single-handed, he conducted a cavalcade of half a dozen horses from Saratoga to New York a lot of horseflesh to keep under control. This was not the bravado of a wild kid, handsome in the devilish way that only the Irish can be. Ryan had been learning about horses ever since he could walk, and perhaps even before that. His father, a horse handler in County Limerick, arrived in America as trainer with a string of racing thoroughbreds and stayed on to become a stable manager in and around New York. Born in Manhattan in 1893, Ryan absorbed horse-lore practically by osmosis. Summers, while still in high school, the tall boy with the big grin and more than his share of blarney worked as coachman for one of the wealthy New York families. Later, resplendent in a brass-buttoned scarlet uniform, he put animals through their paces at the American Horse Exchange at 50th and Broadway. Even his father admitted that few boys-or grown men, for that matter could handle a horse as well as Ryan. Ryan's boss at the Exchange said much the same, but in a slightly different fashion. Since Ryan got a commission on every animal sold, he was naturally eager to show off the horses to their best advantage.

Mr. Norris, his boss, had a matched pair of chestnut hackneys, but Norris looked on them more as white elephants than horses. One of the hackneys insisted on running too close to the wooden shaft that kept him in working position. It was a flaw Norris could not correct. Ryan conceived the simple expedient of switching the horses around. He put the leaner on the outside, where it wouldn't make any difference. By the time Norris realized what Ryan had done, a lady customer came along and bought the hackneys immediately. After Norris made out the bill of sale and the customer departed, he exploded all over Ryan. "You crook!" he shouted. "Where did you learn a trick like that? It's the oldest swindle in the game!"

The Foundling and Other Tales of Prydain

The Foundling and Other Tales of Prydain The Castle of Llyr

The Castle of Llyr Taran Wanderer (The Chronicles of Prydain)

Taran Wanderer (The Chronicles of Prydain) Taran Wanderer

Taran Wanderer The Iron Ring

The Iron Ring The Arkadians

The Arkadians Fifty Years in the Doghouse

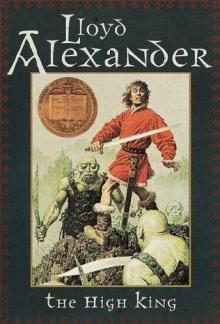

Fifty Years in the Doghouse The High King

The High King The Remarkable Journey of Prince Jen

The Remarkable Journey of Prince Jen The Book of Three

The Book of Three The Gawgon and the Boy

The Gawgon and the Boy The Illyrian Adventure

The Illyrian Adventure Westmark

Westmark The Black Cauldron

The Black Cauldron The Book of Three cop-1

The Book of Three cop-1 Taran Wanderer cop-4

Taran Wanderer cop-4 The Castle of Llyr cop-3

The Castle of Llyr cop-3 The High King (Chronicles of Prydain (Henry Holt and Company))

The High King (Chronicles of Prydain (Henry Holt and Company)) The High King cop-5

The High King cop-5 The Foundling

The Foundling The Castle of Llyr (The Chronicles of Prydain)

The Castle of Llyr (The Chronicles of Prydain)