- Home

- Lloyd Alexander

The Iron Ring Page 5

The Iron Ring Read online

Page 5

Monkey see, monkey do. Monkey's just the same as you. Do like a monkey, be a monkey too.

"Next thing I know," said Hashkat, "I'm a monkey, tail and all. The brahmana vanished, I don't know how or where. I was too busy wondering what had happened to me. Plainly and simply, I've been a monkey ever since."

"He transformed you? Then and there? Unbelievable!" Tamar turned to Rajaswami. "Can this be so? Can such a thing happen?"

"Oh, yes," Rajaswami said. "There have been many similar cases. I've read about them in the old lore. But this can be done only by a great sage, a most mighty rishi who studied long, hard years to gain the secret of such power. The one who transformed Hashkat was no ordinary brahmana."

"A terrible punishment." Tamar put a hand on Hashkat's hairy shoulder. "I'm sorry for what happened to you."

"No need," said Hashkat. "Once I got used to being a monkey, I was grateful to that rishi. It's a relaxing life, without much to do except look for mischief Easier than when I was expected to behave like a warrior. Besides, since I was bigger and stronger than your average monkey, in no time at all the Bandar-loka chose me as their king-which made things even pleasanter."

"You never miss being a human?" asked Tamar.

"A little bit from time to time," said Hashkat, happily scratching himself "A monkey's life has its limitations, but a monkey's dharma suits me very well. What it comes down to is: If it tastes good, eat it; if it feels good, do it. I recommend your trying it. Why go on a journey when you expect to be killed at the end of it? No sensible monkey would consider such a thing.

"I'll tell you what I'll gladly do," Hashkat went on. "The realm of the Bandar-loka is large. Actually, it's anywhere and everywhere we happen to be. Stay with me and I'll share my kingship with you. For one thing, you saved my life, so I'm obliged to you; for another, you're a real king and know more about that business than I do. We'll divide the responsibilities-there aren't many. Nobody can really govern monkeys. Who would want to?"

"That's a generous offer." Tamar smiled and shook his head. "But I mean to keep on with my journey."

"Your dharma must pinch you something awful," replied Hashkat. "You'd find a little elbow room a lot more comfortable. As I said, I admire you, but I don't envy you. In any case, let me do you a service by warning you: Don't follow the river, not at this point. You'll come up against a heavy thorn forest just ahead. You can't get past. Turn off, circle around. Then you double back to the Kurma."

"Turn aside only because of thorns?" Tamar said. "I have an advantage." He pointed at his sword. "I'll cut a passage through them."

"A warrior's way of doing," said Hashkat. "Straight ahead, hacking and hewing. I should have expected that of you. Well then, let me come along and save myself some time."

To this, Tamar willingly agreed; and they set off, leading the horses, with Hashkat scuttling ahead. As the monkey king had warned, a tall curtain of tangled vines soon rose in front of them, stretching in both directions as far as Tamar could see. There were, at least, fewer thorns than he expected.

He hesitated, wondering if there were some better way past the barrier. But since he had already declared his decision, he drew his sword and took a powerful swing at the prickly obstacle. The blade bit deeply into the vines. However, when he tried to pull it loose and launch another stroke, the sword would not come free. He gripped the hilt in both hands and, for better leverage, set a foot against the vines. For all his strength, the sword still would not budge. Nor would his foot.

With a cry of annoyance and impatience, he tried to struggle free. Hoping by sheer force to part the thorny curtain, he grasped the vines, only to find his hands caught as tightly as his foot. Now alarmed as well as vexed, he heaved himself back and forth, thrashing up and down, side to side, which made his predicament all the worse. The vines had captured him.

8. A Miserable Bird

At first, he believed the thorns had trapped him; but Tamar quickly understood otherwise. What held him fast was a sticky juice, a thick resin oozing from the vines. Hashkat scurried to help. Before Tamar could warn him, the monkey was firmly glued and in an even worse plight. His long tail was caught, and his struggles only succeeded in turning him head over heels, dangling upside down.

Rajaswami trotted up. "Good heavens, whatever are you doing?"

"Keep back," Tamar called over his shoulder. "Or you'll be stuck along with us." The sap from the vines was hardening and he saw it was urgent to break free; yet each movement embedded him deeper.

"Acharya, listen to me carefully," Tamar ordered. "We'll need the horses to haul us loose. Fetch ropes from the saddle packs."

"Step lively, too," put in Hashkat, flailing back and forth. "Do you think I enjoy hanging here like a bat?"

"Hashkat first," Tamar said, when Rajaswami hobbled back with the coils of rope. "You'll need to make a harness for him; then hitch the line to Gayatri."

The more the acharya attempted to heed Tamar's directions, the more he fumbled vainly with the cords, and almost tangled himself into them. At last, despairing, he threw up his hands.

"Forgive me, I can't do it," he moaned. "There has to be a better way. Let me contemplate. Something will come to mind." He plumped himself down on the ground, crossed his legs, and folded his arms. "An idea's bound to seize me."

"I'll seize you, if I ever get loose!" yelled Hashkat.

"Acharya, there's no time." Tamar renewed his struggling. The sap had begun to glaze and turn nearly solid.

"There's a sight," declared a familiar voice. "One sound asleep, the other."

"I'm not asleep," Rajaswami broke in. "I'm contemplating." Tamar twisted his head around to stare into the shining black eyes of Mirri. Her long hair had been bound up and she wore the jacket and leggings of a cowherd.

"The other stuck in brambles," she went on, "and still another."

"It's the gopi!" squealed Hashkat. "The one who crowned me with a bucket."

"And-what, the king of the monkeys again?" Mirri set her hands on her hips and cocked an eye at Hashkat. "Well, Your Monkey ship, you've got yourself in a new pickle."

"How did you find us?" Tamar broke in. "What are you doing here?"

"Nanda told me you were heading north along the river," Mirri said, all the while taking stock of Tamar's situation. "You were easy to follow."

With no need for instruction, Mirri looped the rope around Tamar's waist and under his arms, tying the knots deftly and securely, then did the same for Hashkat. Hitching up the horses, she urged them to start pulling. Tamar felt his harness tighten, biting into his chest and almost cutting off his breath. The sap refused to give up its grip; until, at last, one of Tamar's feet came free, then the other. His hands suddenly tore loose and he tumbled to the ground. Hashkat rolled onto the grass beside him. Mirri undid the ropes and lashed them around the hilt of Tamar's sword, and the horses hauled it clear as well. Tamar's hands smarted where shreds of skin had been ripped away. Hashkat had fared worse. Patches of his fur clung to the vines, and a good length of his tail was stripped raw.

"What I don't understand," said Mirri, while Tamar sheathed his sword and Hashkat ruefully eyed the damage to his tail, "is how you got in such a mess to begin with. You should have seen right away you couldn't get through."

"We have to get through." Tamar glared at the brambles as if they were an enemy who had bested him. "I said I would."

"That's how he is," put in Hashkat. "With him, it's a point of honor." "Honor's one thing, stubbornness is another," returned Mirri. "Tut, tut," Hashkat snapped, "that's no way to speak to the king of Sundari." "The what of what?" Mirri rounded on Tamar. "King? You lied to me at the river."

"I didn't lie," Tamar protested. "I'm not the king of Sundari. I gave it up. I turned the kingdom over to my army commander."

"You're splitting hairs," Mirri retorted, eyes flashing.

"Leave that sort of niggling to the brahmanas. I guessed you were at least a warrior, and you said nothing. And what about those fine words you were spout

ing when you were up to your neck in water? I want to know more about this king who isn't a king." Tamar nodded. "Yes. You have every right."

"My boy," Rajaswami interrupted, "this is hardly the moment for amatory confessions. If you don't wish to delay, you'll have to turn aside and circle around these brambles."

"You could go to the river's edge and swim past," said Mirri. "Goodness, no," cried Rajaswami. "I can't swim. That won't do at all." "We could pull you along by your beard," suggested Hashkat. "It looks pretty well stuck to your chin."

"Certainly not," sniffed Rajaswami. "As a brahmana, I insist on maintaining a measure of dignity."

"If you knew as much about country life as you do about your honor," Mirri said to Tamar, "you might have figured how to go at it." She led him to the thorny barrier. "That sticky sap-we have bushes near our village that put out something like it; not as strong, but much the same kind of resin. We collect it and use it in our lamps. It burns brighter than oil. What I'm wondering."

"Set fire to the vines?"

"We can try. See what happens." Mirri strode to a chestnut mare grazing beside Gayatri and Jagati. "Nanda let me borrow a horse," she called back, adding, with a glance at Hashkat: "I'm not a monkey-I didn't steal it."

The girl rummaged through her saddle pack and drew out a flint stone and steel fire-striker. Warning Hashkat and Rajaswami to keep their distance, she knelt at the roots of the vine. Tamar watched closely while she struck a spark that went dancing into the brambles.

The sticky resin hissed and flared. A yellow flame spurted, small at first, then soon rose crackling and licking at the vines, blossoming in all directions. Another moment and the fire was roaring, burning faster than Tamar could have imagined. He flung up his arms to shield his face from the sudden burst of heat.

Mirri, instead of drawing back, seized a dead branch and began thrusting at the blaze, stirring and spreading it deeper into the brambles. She struck away the charred vines and plunged into the gap, driving the fire ahead of her until she had hacked out a flaming tunnel.

"It's burned through to the other side," she called, beckoning to Tamar. "Get the brahmana and the monkey. Blindfold the horses, or they won't go near the fire."

"Gayatri will do whatever I ask," Tamar called back. "The others will follow her."

While Mirri continued to clear away the smoldering vines, Tamar sent Rajaswami stumbling headlong through the passage, then shoved Hashkat after him. He ran back to fetch the horses, who whinnied fearfully but nevertheless heaved their way through the dense, black smoke and showering sparks. At the same time, Tamar heard loud squawks and screeches from somewhere above. Paying no heed, he hastily led Gayatri and the other two steeds into the open air beyond the brambles.

There, Rajaswami was coughing and rubbing his eyes. Hashkat, brushing cinders from his fur, protested that he could have had his tail burnt to a crisp. Mirri, her face smudged still darker by soot, closely observed the smoldering passageway. "Bravely done." Tamar went quickly to her. "You have the heart of a warrior."

"I hope not," Mirri said. She pointed at the brambles. "Look, the flames are dying down. Good. Otherwise, I'd have to find a way to keep them from spreading too far."

"What does it matter? You got us through it."

"Burn down a whole forest for the sake of convenience? That might be a warrior's way, but it's not mine. Strange, though. The vines are growing again."

Even as Tamar watched, new tendrils sprouted, fresh and green, beginning to entwine and fill the burned-out gap. He called over Rajaswami, who peered at the thicket, which had grown almost as dense as it had been.

"Most peculiar," murmured the acharya, as puzzled as Tamar. "Not at all to be expected from ordinary vegetation." He frowned uneasily. "Very odd, indeed. Even magical."

"The door's closed behind us, so to speak," said Hashkat. He glanced at his scorched tail. "That's all right. I don't intend going back. I admit the gopi did us a service, but I might have ended up roasted."

That same instant, before Tamar was aware what was happening, a large and lopsided bundle of ragged feathers came swooping straight at him, beating its widespread wings, buffeting him about the head and shoulders, screeching furiously.

"Shmaa! Shmaa!" squawked the bird. "Enough is enough. I'll stand for no more of your persecution and harassment. You've gone too far."

While Tamar fended off the assault, the bird kept up its cries of outrage and indignation until, suddenly, it flopped to the ground, rolled onto its back, and shut its eyes tightly.

"What is this creature?" exclaimed Tamar, still bewildered by the attack. Mirri and Rajaswami drew closer, to stare curiously at the motionless form. Hashkat squatted down and poked it with a finger.

"It looks like a cross between a buzzard and a trash heap," said the monkey, "whatever it's called."

The bird opened one red-rimmed eye. "Garuda is what it's called. Not that it matters. Who cares? It's just poor, helpless Garuda. Call him a buzzard, call him trash, whatever you please. Go ahead, you grinning idiot, aren't you going to kick me when I'm down? You might as well. You've done your worst already."

"What are you talking about?" Tamar knelt beside the disheveled bird, who rolled over and stood up on a pair of scabby legs. "We've done nothing to you."

"Nothing?" Garuda snapped his hooked beak. "Of course not. Nothing to make you lose a wink of sleep, nothing to weigh on your conscience for even an instant. No, you've only burned up my nest, destroyed my home-Well, this time I've lost patience. You've driven me past endurance."

"I'm sorry," Mirri began, reaching out a hand to calm the bird. "I didn't know you had a nest there."

"A likely story," Garuda flung back. "I should believe that? Why do you think I built it in the thorniest place I could find, and avoiding that horrible goo? To get a little peace and quiet. Don't tell me you-and he, and the brahmana, and the scruffy-tailed banana-gobbler didn't plan the whole thing. What's to do for sport this morning? Why, let's go burn Garuda's home to cinders.

"You aren't the only ones after me," Garuda pressed on. "Just the other day, I'm perched on a tree, minding my own business, when some malicious fool shoots an arrow at me. Missed me by a hair. I flew off as fast as I could before the numbskull tried again."

"So, he's the one who woke up the snake and got me in trouble," said Hashkat. "I shot the arrow," Tamar said. "I was aiming at the tree; I saw no bird."

"Aha!" cried Garuda. "You're all in it together, just as I thought."

"He's quite mad," Hashkat muttered to Tamar. "Leave him. Let's be on our way."

"Oh, no, you don't!" cried Garuda. "You wrecked my home. You owe me. You owe me plenty for all the pain and misery you've caused."

"I regret to say," Rajaswami told Tamar, "accident though it was, the young lady acted for your benefit, so you must bear some responsibility. And you were the one who disturbed him in the first place. As he claims, you owe him something: A king never forgets To pay his debts.

"He's not a king anymore," Hashkat protested. "Let this moth-eaten sack of feathers build another nest. What else does he have to do with his time? Or, he can go roost with his fellow vultures."

"First, you call me a buzzard-now, a vulture!" cried Garuda, so furious that he was quacking like a duck. "You don't know who you're dealing with. I'm an eagle!"

9. Lost and Found

"Eagle?" Hashkat slapped his knees and hooted with laughter. "What, did a wandering rishi lay a curse on you, as one did to me when I was a human?"

"So that's what happened to His Monkey ship," Mirri said apart to Tamar. "Somehow, I'm not surprised."

"Whatever you did, I'm sure you deserved to be cursed for it," snapped Garuda. "I'm an eagle now and always have been." The bird shook his wings and looked down his beak at Hashkat. "I'll have you know, in my better days-ah, ah, better days they were-I served a mighty king."

"As what?" Hashkat stuck out his tongue. "A feather duster?"

"His trusted messenger," Garuda re

torted, with an air of shabby dignity. "No errand was too difficult or dangerous. One day, His Majesty sent me on a most important mission.

"A treacherous servant had stolen an extremely valuable gem and given it to a rakshasa, an evil demon, in exchange for the gift of eternal life. You can see how precious the jewel was, to be worth that sort of bargain. The rakshasa didn't keep his word."

"They never do," put in Rajaswami. "When will people realize there's simply no dealing with them?"

"Feel free to interrupt whenever you please." Garuda glared at the acharya. "I'm only telling you the story of my life.

"As I was saying Eh? Where was I?" Garuda blinked and wagged his head. "Ah. Yes. The servant came to a messy end. The rakshasa and the jewel vanished.

"In time, my royal master learned the rakshasa had hidden the gem in a mountain cavern, protected by a ring of fire. Who had strength even to reach that cavern? Or, once there, courage to risk the flames?"

Garuda paused and glanced around. "I just asked a civil question. It's too much, I suppose, to hope for a civil answer."

"You were the one," Mirri said, with an encouraging smile. "The king sent you, of course. Then what?"

"Thank you for your interest," said Garuda. "Yes, I went. Oh, my wings-they ache when I think of it. How long I flew over peaks poking up at me like daggers, through rain and hail, sleet, snowstorms."

"All right," said Hashkat. "How long?" Garuda rolled his eyes. "I can't remember. But, at last, I found the cavern.

"And there was the gem in the midst of a circle of flames. Not for an instant did I hesitate. I plunged through oh, the pain, the pain! I could smell my feathers burning, my talons shriveling, but I snatched up the gem in my beak. Hard to believe such a small ruby could be worth so much. For a moment, I wondered if it was the right one. No mistake. As I'd been told, it had a lotus flower carved on it." Tamar stiffened. He was about to interrupt, but Mirri put a finger to her lips. Garuda went on:

"I flew from the cavern. The fire had scorched and blackened my golden plumage, my tail feathers were little more than a charred stump. No matter. I had served my king well, proved worthy of his trust, done as he commanded."

The Foundling and Other Tales of Prydain

The Foundling and Other Tales of Prydain The Castle of Llyr

The Castle of Llyr Taran Wanderer (The Chronicles of Prydain)

Taran Wanderer (The Chronicles of Prydain) Taran Wanderer

Taran Wanderer The Iron Ring

The Iron Ring The Arkadians

The Arkadians Fifty Years in the Doghouse

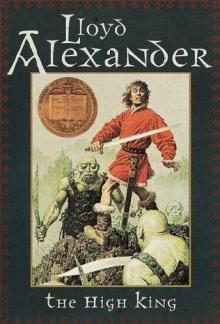

Fifty Years in the Doghouse The High King

The High King The Remarkable Journey of Prince Jen

The Remarkable Journey of Prince Jen The Book of Three

The Book of Three The Gawgon and the Boy

The Gawgon and the Boy The Illyrian Adventure

The Illyrian Adventure Westmark

Westmark The Black Cauldron

The Black Cauldron The Book of Three cop-1

The Book of Three cop-1 Taran Wanderer cop-4

Taran Wanderer cop-4 The Castle of Llyr cop-3

The Castle of Llyr cop-3 The High King (Chronicles of Prydain (Henry Holt and Company))

The High King (Chronicles of Prydain (Henry Holt and Company)) The High King cop-5

The High King cop-5 The Foundling

The Foundling The Castle of Llyr (The Chronicles of Prydain)

The Castle of Llyr (The Chronicles of Prydain)