The Foundling and Other Tales of Prydain

The Foundling and Other Tales of Prydain The Castle of Llyr

The Castle of Llyr Taran Wanderer (The Chronicles of Prydain)

Taran Wanderer (The Chronicles of Prydain) Taran Wanderer

Taran Wanderer The Iron Ring

The Iron Ring The Arkadians

The Arkadians Fifty Years in the Doghouse

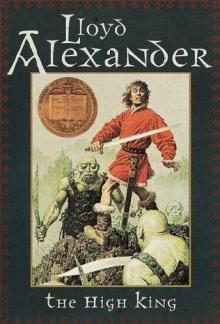

Fifty Years in the Doghouse The High King

The High King The Remarkable Journey of Prince Jen

The Remarkable Journey of Prince Jen The Book of Three

The Book of Three The Gawgon and the Boy

The Gawgon and the Boy The Illyrian Adventure

The Illyrian Adventure Westmark

Westmark The Black Cauldron

The Black Cauldron The Book of Three cop-1

The Book of Three cop-1 Taran Wanderer cop-4

Taran Wanderer cop-4 The Castle of Llyr cop-3

The Castle of Llyr cop-3 The High King (Chronicles of Prydain (Henry Holt and Company))

The High King (Chronicles of Prydain (Henry Holt and Company)) The High King cop-5

The High King cop-5 The Foundling

The Foundling The Castle of Llyr (The Chronicles of Prydain)

The Castle of Llyr (The Chronicles of Prydain)